We work with many dogs with varying degrees of anxiety. For example, my favorite breed, the German Shepherd Dog, is supposed to be naturally unshockable. This is based on the breed standard and origination. However, I work with many German Shepherd Dogs because they are fearful in some way. But fear isn’t just rampant in German Shepherd Dogs. This affects all dog breeds in the United States. I once worked with a Belgian Malinois who bit people coming to the home out of fear. This is equally disturbing. Fear and anxiety in dogs are some of the most common challenges we are contacted for. The reasons for this fear epidemic in dogs are multifold. But generally, they include one or multiple of the following elements.

Causes of Fear and Anxiety in Dogs

- Separating a puppy from the mother too early—before seven weeks.

- Mismanagement of the fear phases during puppy development—there are usually three.

- Poor breeding practices create genetically unsound dogs and psychologically fragile nerves.

- Abandonment by the previous owners, ending up in a shelter and being rescued by a new family—the lucky ones.

- Trauma and injury from dog attacks.

- Lack of clarity about their environment, including the home.

- Frustration from their leash and collar. Especially if we regularly drag them closer toward things they are uncomfortable with.

- Interpreted obedience instead of literal obedience—that’s a whole separate discussion.

- Environmental stress. This can include having children, adding a pet, losing a pet, moving, and changing schedules. As well as having less time to spend with your dog, dating someone new, and so on.

- Failure to help dogs develop psychological strength during puppy development. And failure to teach stress management strategies.

The following list is not all-inclusive, and the differences between these behaviors are somewhat fluid. It would be incorrect to refer to these as ‘types’, but we help many client dogs with these.

Common Symptoms of Fear and Anxiety in Dogs:

- Biting and/or attacking unfamiliar visitors to the home. Or anyone else who tries to touch them (incl. vets, groomers, and alike).

- Barking at unfamiliar things and strangers without attacking.

- Showing skittish behavior around unfamiliar things. For example, hiding behind their owners or straining on the leash to avoid or escape.

- Experiencing separation anxiety or containment phobia. As a result, dogs howl, bark, whine, self-mutilate, destroy the home, and so on.

- Anxiety urination when approached or surprised.

- Trembling, shaking, rolling over, and/or shutting down when stressed.

- Lying lethargically in place and suffering in silence when under duress. This is referred to as learned helplessness.

In this article, I’ll explain what goes on internally when you see fear and anxiety in dogs, Also, I will touch on some general concepts around building up your dog’s confidence and increasing its stress resilience.

Dogs Have Emotions

You can still find places on the internet and dog trainers stuck in the 19th century who claim otherwise. But at this point, it is a well-established biological fact that all mammals have emotions. If you are interested in exploring this in-depth, I recommend the book Affective Neuroscience by Jaak Pankseep, 2004—a very technical but fascinating read. My explanations about the biological underpinnings of fear and anxiety in dogs are based on this book. In addition, I also recommend Behave by Robert M. Sapolski, 2017.

Understanding Fear and Anxiety in Dogs on a Biological Level

Grossly simplified, we have three separate brain layers. They all evolved over time. The base layer is the evolutionarily oldest brain layer in all animals—including humans. The base layer oversees auto-motor functions. When we are cold, shiver, and our body hair stands up, the base layer sends neurological signals to the body to cause this effect. Reptiles through mammals all have this brain layer—basically all non-plant life. In addition, habits also reside in this area. This layer is often referred to as The Reptilian Brain.

The next brain layer evolution produced is the emotional layer—the limbic system—which consists of various emotional systems. The limbic system is present in all mammals: mice, horses, humans, dogs, and so on—all mammals have this brain layer and experience emotions. They are displayed to the outside world in different body language, but the internal experience is identical in all mammals. So, when we talk about fear and anxiety in dogs, it is no different from how humans experience fear. We may have a broader behavioral response repertoire, but the internal experience is the same. Understanding this allows us to relate better to our dog’s experience under stress.

The Emotional Systems (The Limbic System)

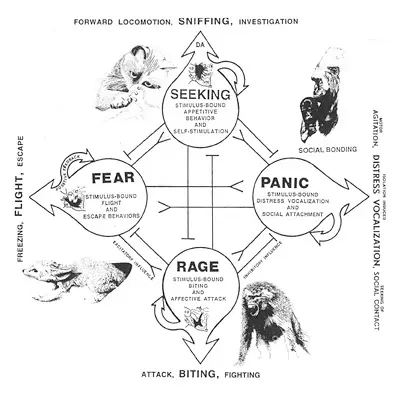

Some emotional systems are more researched than others, but we understand where the main emotional areas are located in the brain. We can attach electrodes to these areas and measure brain activity, for example, during a fear experience. Or, in turn, (in Dr. Frankenstein’s laboratory) stimulate the brain’s fear center, and the person or animal would tremble in fear for no other reason than the stimulation of that brain area. The main emotional systems we understand well, on the positive emotional side, are PLAY, CARE, and LUST —and on the negative emotional side: RAGE, PANIC, and FEAR. In addition, there is another emotional system called SEEKING—more on that later. The emotional layer also communicates with the base layer. If an emotion should generate a physiological response in the body, the emotional layer delegates that to the base layer.

Nature vs. Nurture

In addition, animals do not need to learn to experience and express fear, anger, pain, pleasure, joy or play in simple rough-and-tumble ways, even though these processes are modified by learning. All these emotions are innately available from birth.

All behavior in mammals, at least from birth, is a mixture of innate and learned components. Studies suggest that approximately 50% of basic human behavior can be attributed to genetic factors, while about 50% can be attributed to learning.

The Seeking System

Animals do not have to learn to search their environment for items needed for survival; they are hard-wired to do so. Although, they do need to learn exactly when and how to search. In other words, the “seeking potential” is built into the brain, but each animal must learn to direct its behaviors toward the opportunities available in the environment. The brain system responsible for this is called The Seeking System. The Seeking System drives motivation. It is also where dopamine is released.

The Emotional Counterparts

A major opponent emotional process to the innate SEEKING impulses comes from the RAGE system. The RAGE system energizes the body to angrily defend its territory and resources. The RAGE system starts at the lowest end with frustration and can escalate to extreme aggression, aka rage. Generally, frustration starts when someone is prevented from accomplishing something. For example, when we are stuck in traffic, we become frustrated, and it can escalate into road rage.

Another brain system central to generating a major form of trepidation that commonly leads to freezing and/or flight response is called the FEAR system. This brain area handles all emotions related to concerns over our safety. So, when a dog experiences any type and level of fear, it is because the neurons in the FEAR system of the emotional layer are firing on all cylinders.

The brain system that generates feelings of loneliness and separation distress is called the PANIC system. For example, it would activate when we felt a group of people was talking about us negatively or in a child when its parents walk away from the playground to the car, leaving the kid behind.

The third—and for now evolutionary highest—brain layer is the prefrontal cortex, the “executive functions” part of the neocortex. This layer is most developed in humans, but many—not all—animals have it to some extent. Dogs have a prefrontal cortex, but it is smaller than in humans. This is the part of the brain where planning, goals, and actions happen. The human prefrontal cortex is why we have self-driving cars and monkeys don’t. The neo-cortex also communicates with the emotional layer and the base layer.

Blue Ribbon (Grade A) Emotions

The four most-studied systems are an appetitive motivation SEEKING system, a RAGE system, a FEAR system, and a PANIC system.

SEEKING System: helps elaborate energetic search and goal-directed behaviors.

RAGE System: easily aroused by thwarting frustrations,

FEAR System: designed to minimize the probability of bodily destruction.

Separation-Distress PANIC System: especially important in the elaboration of social-emotional processes related to attachment.

The mammalian brain’s four major emotional systems are also called “Blue-Ribbon, Grade A” emotions.

The SEEKING system is a neuronal network promoting survival abilities. This system makes animals intensely interested in exploring their world. It also excites them when they are about to get what they desire. It eventually allows animals to find and eagerly anticipate the things they need for survival, including food, water, warmth, and their ultimate evolutionary survival need, sex. In other words, it helps fill the mind with interest and motivates organisms to move their bodies effortlessly in search of the things they need, crave, and desire. In humans, this may be one of the main brain systems to generate and sustain curiosity, including for intellectual pursuits. This system facilitates learning, especially how to locate and obtain material resources.

Rewards vs. Rewards Prediction

Behaviorists view attributes like quality, quantity, and delay of reward as the incentive properties of a reward. They ignored how highly desirable objects stimulate the nervous system internally.

However, measurements of cellular activity and dopamine release indicate mammals focus more on reward prediction than rewards themselves.

We can measure and/or stimulate these hard-wired brain systems physically.

SEEKING system behaviors: forward locomotion, sniffing, investigating

FEAR system behaviors: freezing, flight, escape

PANIC system behaviors: agitation, distress vocalization, social contact

RAGE system behaviors: attack, biting, fighting

Negative and positive emotional systems are mutually exclusive. The distribution of activity between both sides always adds up to 100%. For example, if the FEAR system in a dog is 20% active, a positive system like NURTURE can only be 80% active.

Further, as the SEEKING System turns on, it pulls the dog out of a negative emotional system and moves it to a positive emotional system. The goal is to turn off RAGE, FEAR, and PANIC and turn on PLAY, NURTURE, and LUST.

We Can Activate the SEEKING System in One of Three Ways

- Desire (for something good)

- Expectation (of something good)

- (Non-threatening) Novelty

The general approach to utilizing this understanding in training is to first block negative emotions (not correcting them). Second, encourage positive emotions. And third, trigger SEEKING to help transition between the emotional states.

With repeated execution of this process, the neurons in the brain areas of the negative emotions fire less frequently. As a result, those neurons diminish, which makes these systems harder for the dog to access with enough repetitions. By encouraging positive emotions, the neurons in those brain areas become more pronounced, making those systems easier to access. This process rebuilds the neural pathways and restructures the brain to seek positive emotions over negative ones, arguably creating a more natural, healthy brain state. The previous behaviors go extinct with repetition, and a new ‘positive’ default activates.

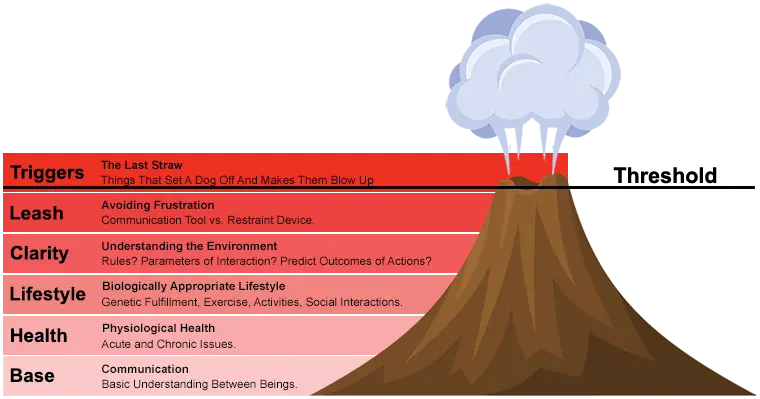

Lowering your Dog’s Stress Level is Step One

Obviously, by now, it is clear that this is a gradual process and takes time. Also, dealing with the actual fear response is not the first step. The stimulation that causes your dog to act fearfully is just the tip of the iceberg—referred to as a trigger. When a dog is afraid of skateboards and acts fearfully—including attacking the skateboard as a defensive measure—the skateboard is the trigger. However, many other components are building up to the skateboard being that scary, which have nothing to do with the trigger itself. Dogs experience significant stress in their daily lives, and we acknowledge it in dogs in layers that stack upon each other and build up. If all the added stress becomes too much, your dog reaches its threshold and shows a fear-driven response.

The Layered Stress Model by Chad Mackin describes this process in detail. You can read more about it in this blog post and/or listen to the corresponding podcast.

Reducing Fear and Anxiety in Dogs

Step-by-step, we build up your dog’s confidence and teach stress management skills to maneuver the world without fear.

The first step is gaining the dog’s trust. Most dogs have been fearful for quite a while, so trusting a stranger doesn’t come easy. But it is a vital first step, and we must take the time to do so. There are no shortcuts. Without trust, failure is certain. Also, overcoming a smaller stress event—like trusting us—will work towards building confidence to overcome larger stress events later.

Second, we develop a confidence-building game that speaks to your dog’s genetic preferences and lays the foundation for everything else. Through this game, we can build trust, increase confidence, and teach cooperation, rules, and consequences, all outside the context of any particular stressors.

Third, we build a stronger bond between you and your dog, where your dog learns to trust you more and understands that you got its back, and will advocate for it when necessary.

Dealing with the Remaining Triggers

By now, your dog will already be much calmer and can handle more stressors than before. As your dog becomes more confident, its fear reactions will diminish. Your dog will feel less threatened by what scared it initially. However, if your dog still reacts to some triggers, the reaction will be much milder and more manageable than initially.

Any remaining fear trigger reactivity will be addressed through faith-in-handler drills, counter-conditioning, desensitization, guided exposure, and penalties for dangerous behaviors we can’t allow. Trigger work is generally the most stressful part; most dogs can’t handle it at the outset. We work on triggers only if we have to and only once your dog is already more confident. Your dog will be more successful in this way. Too many trainers want to jump straight to these strategies, which will cause too much stress on your dog to be successful. With a gradual approach, your dog gains confidence at its optimal pace. We want to avoid overwhelming your dog. Every successful step forward in dealing with something mildly stressful builds confidence in your dog and helps you take on bigger challenges.

Play the Audio