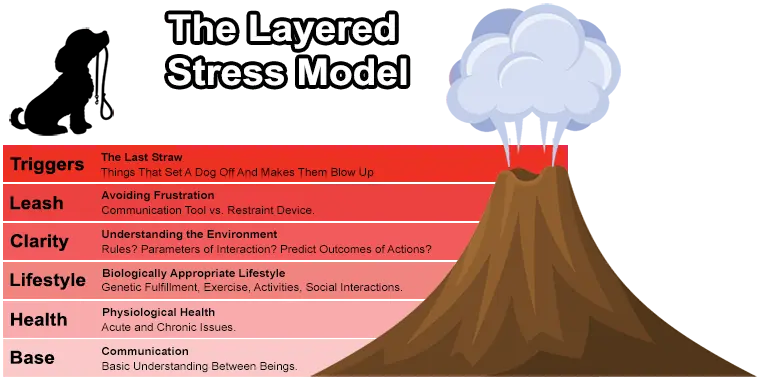

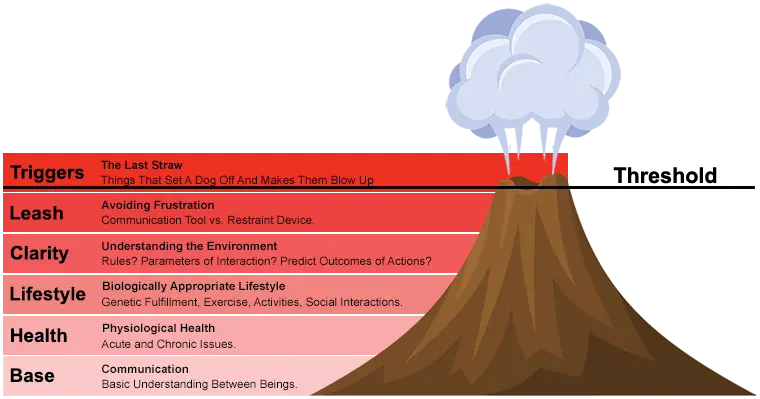

The Layered Stress Model is a framework to understand what causes stress in dogs and, as a result, contributes to undesirable reactions. Like people, dogs can only handle so much stress per day. Once it becomes too much, they snap as any person would. To my knowledge, The Layered Stress Model has its early origin with Dr. Jean Dodds. She is a well-known holistic veterinarian in the United States. But Dr. Dodds didn’t present it in this refined version. She had a rudimentary outline for the concept of stress accumulation. A fellow dog trainer, and friend, Chad Mackin, used her foundation as a starting point and refined it into the version I am outlining in this article. I consider it The Layered Stress Model by Chad Mackin.

Impulse Control is Finite

Impulse control is a very energy-consuming activity. To not react when something goes wrong takes impulse control. There is nothing that consumes more energy in a brain than impulse control. That’s why we, and dogs (and many animals), can only tolerate a limited amount of disorder and stress daily.

Imagine the following scenario. You wake up in the morning with a headache. When you get out of bed, you step on a lego block. Next, you go to the bathroom and notice you ran out of toothpaste. When you enter the kitchen, you have no tea or coffee left. Then, you get a speeding ticket on the way to work. First, that’s a crappy day. Second, I would not want to be the first person to talk to you when you get to the office.

Stress Accumulates

The point is this, any single one of these events is unpleasant but not the end of the world. But accumulating more stress factors makes you burn through your impulse control before you even start work. All these stressors pile on top of each other and add up until you reach, and go through, your threshold. Your threshold is unique to you. It is your genetic limit of the maximum amount of stress you can handle before you blow up. As long as your stress level remains under your threshold, you can control your impulses. Once your stress level passes through your threshold, all bets are off. This is the same for dogs; just their stressors are different. The Layered Stress Model describes dog’s stressors.

Layered Stress Model Examples

Let’s look at a few examples. For a dog, this can mean that distractions become too intense for it to follow obedience commands still. Fearful dogs can become too stressed and shut down or blow up. It can be that an aggressive dog acts upon its triggers. Or, a dog that is not feeling well can react towards a stimulus one way, although it would handle things differently if it were feeling better. In short, when the stress gets too high, the dog fails.

I hope this illustrates that if we only focus on the triggers upon which our dog reacts, we make it much harder for our dog and ourselves to better deal with the environment. The better approach is to address all the different stress elements of The Layered Stress Model before working on any trigger reactions.

The Base Layer of Stress

Humans and dogs are different species. There is a natural communication barrier. We don’t always understand our dog, and our dog doesn’t always understand us. This tends to become less of a factor the longer we know each other, but it never goes away completely. Not being understood causes stress. Imagine you were dropped off somewhere in the countryside in China where no one spoke your language, and you didn’t have your phone. It would be pretty stressful trying to get out of there without being able to communicate. That is how your dog often feels. It’s stressful.

Paying attention to what your dog is trying to tell you can help tremendously. And as I said, over time, it usually becomes less of a factor. Nonetheless, the base layer of The Layered Stress Model should not be ignored.

The Health Layer of Stress

Health affects behavior. If a dog has a health issue, its threshold will be way lower than if they were healthy. A dog can’t tell anyone if it isn’t feeling well, and you will only notice conditions once they get bad enough to show symptoms. Dogs are predators and, by default, hide their ailments as long as possible.

Consider how you are when you have a headache. I don’t want to hear anything from anyone until it’s gone. What if your dog had a headache? It couldn’t tell you. How would you know?

We all know that acute conditions can affect behavior. The classic example: a dog with an injured leg snaps at you when you touch that leg. That’s obvious. But people are less aware of how chronic health issues can affect the health layer of stress in a dog.

An allergy that leaves a dog itchy. An inflamed stomach from food intolerances. Neither of these would be bad enough for us to see physical symptoms, but they would add to their stress! Also, medications can increase health stress in a couple of ways. Some medications cause emotional side effects, and many antibiotics cause stomach distress. That can easily make dogs a little snarkier.

Less frequent examples are physiologically impaired dogs with thyroid issues, neurotransmitter dysregulation, and so forth. Those would drastically affect behavior.

What to Look For

You are keeping your dog in excellent health. Regular vet care. Good food. Grooming and hygiene. All that good stuff. And I know discussing health during a behavior discussion is a little like that phone call to the IT department when they ask you, “is it plugged in” or “is the power on?” Yes, it makes you want to punch them, but it IS essential. They can’t help you if the thing isn’t plugged in. It’s the same here. If a dog isn’t in good health, none of the strategies to manage a dog’s stress will get the dog’s stress below its threshold.

A few indicators to keep an eye on. Is your dog drinking more or less? Eating more or less? Sleeping more or less? Does it scratch itself more than usual? Any changes in the urine’s color or the stool’s consistency? Lethargy? Any slight limping? Less fluid motion when walking or running? Any sudden, unexplained behavior changes? These are just a few examples that can indicate underlying health issues.

Any time you see a sudden change in behavior in your dog, please take a moment and look at the health layer. Skipping this step and assuming health may drastically affect the outcome of any training protocol you try. It should always be the first assessment in The Layered Stress Model.

The Lifestyle Layer of Stress

Everyone desires a genetically fulfilling lifestyle with biologically appropriate activities. If dogs had the world to themselves, they would search, stalk, chase, fight, consume, celebrate and mate. They wouldn’t go walking around the block or practicing heeling. Even if you take your dog for a six-mile walk daily, you are still only providing a fraction of what your dog naturally would do and enjoys. Finding biologically fulfilling activities for our dogs keeps them psychologically healthy. Our job is to figure out what our dog likes and how we can provide that either directly or through suitable surrogate activities.

Genetic Fulfillment Matters

Imagine you are an avid hiker who hits the trails every weekend, or you love playing an instrument or playing a sport with passion. Any activity that fulfills you and makes you happy. Now, you have an accident, break something, and can’t do it for 2-3 months. How would you feel? Not being able to do what you are passionate about doing is frustrating. It creates stress and a short fuse. Again, this is no different with dogs. They are predators who love to hunt. They don’t get to do that with most of us. Hence, providing an appropriate outlet that still gives them what they are genetically craving keeps their stress down and makes them much happier.

Dogs tend to find other outlets to fill that void without genetically fulfilling activities. We tend not to care much for what they come up with. Providing your dog with what it needs keeps them out of trouble and reduces stress. You can read more details on this in our article Dog Misbehavior.

The Brahimil Commission on Animal Welfare Defines a Good Lifestyle as:

- Absence of Hunger and Thirst (this is self-explanatory)

- Freedom from Discomfort (this, too, is self-explanatory)

This generally means prolonged discomfort. No one is always comfortable. Short-term, temporary discomfort is part of life and unavoidable.

- Absence of Fear and Distress (this can be natural evolutionary fears or learned fears)

The emotional causes can be different for each dog. One activity may distress one dog and not bother another. Getting to know your dog helps you understand what causes them distress. “Freedom” from these fears and distresses doesn’t necessarily mean avoiding them. This may mean teaching them they don’t need to be afraid of them. It is up to you to understand your dog and decide what they need. You also must develop the kind of relationship required to guide them through their fears.

- Freedom to Express Normal Behaviors (this is the one everyone is familiar with)

Dogs need to search, stalk, chase, fight, celebrate and consume—in short, hunting activities. Most dogs prefer some of these over others. Breeds vary for a reason. You must figure out what behaviors and activities are fulfilling to YOUR dog and find a way to provide them—or surrogate activities, that fit with your lifestyle.

The Clarity Layer of Stress

Every creature functions best when the parameters of interaction in its environment are understood. Clarity about what actions lead to what responses are essential for peace of mind. If you walked into a room and randomly received an electroshock without warning, you would be on edge from that moment forward. You couldn’t predict what caused it and would be unable to prevent it from happening again.

However, if you only received an electroshock when you touched a button that reads “Don’t Touch,” you could relax again after that mistake. You would understand you touched something you shouldn’t have and had a fair warning. That one is on you. You’d have clarity in scenario two. This is an extreme example. But this is no different if you randomly yell at your dog for doing things you don’t like without ever teaching it what is off-limits. Lack of clarity causes stress.

The Need For Clarity Varies

Every being requires a different level of clarity to maneuver the world safely. Structure is one way to provide clarity but not the only way. Some dogs need a lot of clarity, while others need little to no. The goal of structure should be to provide clarity. As understanding develops, structure can be reduced without the dog losing clarity. One example is obedience commands. Most obedience is interpreted and not literal. Dogs often lack clarity on what is included with a command and what is optional.

An example would be the difference between the commands “off” and “down.” These commands tend to be used very inconsistently. If you tell your dog to go “down” when it is lying on the sofa, it’s confusing. It is already in a “down.” That doing that on the sofa was wrong wasn’t understood. If commands are used inconsistently, there is no clarity. We are asking the dog to guess and get upset when it guesses wrong.

It should be clear how this adds stress. Interpreted obedience adds stress due to a lack of clarity. Only literal obedience can reduce stress. Without clarity, a dog is not disobedient, it just guesses wrong. Obedience should only be used if it provides more clarity.

The Leash Layer of Stress

Most dogs find leashes annoying, preventing them from doing what they want. Leashes are frustrating because they stop the progression. Whenever a dog (or a person) is prevented from proceeding somehow, it causes frustration. Frustration is the first step of rage. Nothing good comes from that. Of course, we can use some forms of frustration to increase drive and determination, but unintended forms of frustration are unproductive during training. Leash restraint creates negative frustration unless we habituate our dogs. Most dogs develop a relationship of disregard or disdain for the leash and collar if we don’t. By habituation, we can change this perception of the collar from an annoying restraint device to a helpful information tool.

Triggers

After reducing a dog’s stress layers and possibly teaching them to relax on cue, they may still struggle with specific triggers. In that case, several different approaches can help with these issues:

- Punishment: When done correctly, this will be the fastest way to end an unacceptable behavior. However, it doesn’t make the dog feel better about the situation, but it will stop the nonsense. Punishment should generally be the last step in a training program to help a dog improve unless there is no alternative to starting there.

- Desensitization: This process makes a dog look at something differently. It would be accomplished by playing in proximity to a trigger or feeding a dog through a situation if possible.

- Building Trust: Making your dog trust you more through situation-specific Faith-In-Handler exercises.

- Counter-Conditioning: A process of teaching a behavior incompatible with the trigger reaction.

- Flooding: Prolonged exposure to a trigger or situation. This is also called “exposure” and means “deal with it.” With the right dog, it can be the fast answer to a specific problem. However, with many dogs, this is problematic.

Understanding the impact of stress on dogs is essential when addressing fear issues. Read more in our article Fear and Anxiety in Dogs.

Play the Audio