My name is Ralf Weber, and I am a certified professional dog trainer. I am a certified Training without Conflict™ trainer (TWC CPDT) and a certified advanced trainer by the IACP (IACP CDTA). I am a professional member of the International Association of Canine Professionals (IACP) and an evaluator for the American Kennel Club’s (AKC) Puppy Star, Canine Good Citizen (CGC), and Community Canine (Advanced CGC) programs. Further, I hold a broad range of other certifications. I am also the author of the canine behavior book If Your Dog Could Talk. In addition, I am the owner of Happy Dog Training. I have been working with dogs for over 20 years.

I am not listing my credentials to brag. In contrast, I want to highlight that I have the experience and background to write about dog training. I believe it is vital for readers to know if an author is qualified. Passing off unqualified, personal opinions as knowledge is a far too common problem these days.

The only thing two dog trainers will ever agree on is that a third trainer has no idea what they’re doing.

– unknown

This joke holds a lot of truth. There are as many training methods and philosophies on dog training as there are dog trainers. There is no limit to the number of training methods trainers advocate for. Common names are clicker training, treat-based training, positive-only training, force-free training, reward-based training, dominance training, relationship-based training, play-based training, and so on. What should a dog owner choose? What is the right way? It can be confusing.

The Challenge for Dog Owners

Unfortunately, many dog trainers and dog trainer schools contribute to this confusion. They fail to understand the fundamentals and further mislead the public in their advertising. The correct terminology also escapes many. As a result, they throw words around they don’t fully understand. Furthermore, distinctions between methods, concepts, components, and tools in dog training are often grasped poorly.

For example, the most misunderstood and misused term in dog training is probably positive reinforcement. Many trainers claim this to be their method of training. However, positive reinforcement isn’t a training method. It is a component of operant conditioning—a core principle in dog training. Trainers who claim only to use positive reinforcement fundamentally don’t understand their profession and how the things they do are called—more on this later. If you are interested in diving deep into this topic, please read my article on Positive Dog Training.

What further adds to the confusion is that everybody has an opinion on dog training. Your neighbors, gardener, coworkers, relatives, and so on. However, most people don’t have any skills or knowledge that would lend credibility to their opinion. They are their opinions. Probably well-intentioned in most cases but ultimately meaningless and not rooted in knowledge.

Consider the Dog

Another fallacy many people—and unfortunately many dog trainers—make is to believe that all dogs respond to and are motivated by the same things. This is not so. An approach that worked for one dog doesn’t necessarily work for another. Fellow dog owners who had success with a particular approach often want to be helpful and share their success stories. But that doesn’t mean the same approach will work with your dog.

I recommend only seeking dog training advice from professionals who work with dogs for a living, not random dog owners or online discussion forums. Please review my article How to Hire a Dog Trainer for more guidance on selecting a knowledgeable dog trainer.

I will provide a high-level overview of dog training in the following sections. I want to provide an outline and general guidance. This is not intended to be a complete list of everything. Also, all areas have more facets than one article could ever cover. Entire books could easily be written for each section. Dog training is an art and a science.

1. Motivation

Without motivation, you have nothing. It doesn’t matter what else you do. If the dog is not motivated to work, the result will be ugly. Too often, the dog is blamed for being difficult or uncooperative. Next, the trainers often resort to compulsion to make him do it—the typical response of balanced trainers. Or, you are told that your dog can’t be trained—a typical response of the force-free community. Both are unqualified responses.

As so often, the answer lies elsewhere entirely. If a dog fails to perform a task, there are only three possible reasons for that:

- First, the dog doesn’t understand what you are asking it to do. It doesn’t matter how much we think it should. The number of repetitions does not make up for poor instructions.

- Second, the dog understands but is incapable of doing it. It could be temporary. For example, if the dog’s hip is sore, asking it to sit will be met with resistance. It hurts. You can’t blame him for that.

- Third, the dog has no reason to do it. There is zero motivation to cooperate. I don’t work for free, either. Do you?

In all three cases, the fault lies with the trainer, not the dog. We must give our dogs clear instructions, ensure our request is fair and motivate them to work with us.

2. Clear Communication

Providing clear, consistent communication during training goes a long way. We must aim to present the dog with clear instructions, help where necessary, and guide them to success. A good trainer is an excellent coach to the dog.

A common way to provide clear communication is through markers. Markers are signals that the dog should pay attention to either to do something or is done doing something. Signals can be kinesthetic, auditory, visual, olfactory, or gustatory. The most commonly used signal may be the sound of a clicker—an auditory signal. But using words instead of a clicker gives you more variety and is way easier. The clicker advocates (aka The Karen Pryor Academy) have a study on their website claiming to prove the superiority of the clicker. Read it; it’s pretty laughable in its setup and ‘findings’. It couldn’t be reproduced and has never been independently validated. A more scientific study with a cleaner setup found no measurable difference between a clicker and words. That also makes more sense, as dogs are smart.

Common Verbal Signals:

- Yes — often used as a success signal. It tells the dog “Mission Accomplished” and indicates a reward is coming.

- Good — often used as a continuation (aka “keep going”) signal. It tells the dog it is on the right track and moving towards a “yes.”

- Ah-Ah — often used as a discontinuation signal. It tells the dog it is on the wrong track, moving further away from a “yes.”

- No/Bad/Wrong — often used as a punishment signal. It tells the dog it will be punished for what it just did. It was unacceptable.

- Okay — often used as a release signal. It tells the dog we are done with the exercise. It is free to do what it wants.

Trainers use many other signals. It is not important what signals a trainer uses. It matters that they are used consistently with the same meaning.

Dogs love interacting with us. It is our job to make that fun and productive for all involved. The interaction should be engaging, focused, and straightforward. Avoid confusing and mixing signals and words. If we are confused, our dog will be confused.

3. How Dogs Learn

In training, dogs often learn new behaviors or commands through classic and operant conditioning. But trainers also use, and dogs can learn through observation, mimicking, shaping, capturing, and other ways. The question is often not can a dog learn it one way or another, but what is the most effective way to teach a particular behavior? What produces the result the fastest and in the most reliable manner?

Before We Dive In

Before we go any further, I want to be very clear on one thing. None of what you are going to read here should be in any way, shape, or form interpreted or used to justify animal abuse. There are plenty of poor examples on social media who show off their dog abuse with prongs or electric collars in the name of behavior training. They have many online followers and are pretty proud of themselves. I despise these dog abusers more than you can imagine. These are not dog trainers. They are a disgrace to our profession. The behavior of these people will get valuable dog training tools banned, and dog owners who can’t get help will ultimately suffer the most.

When I talk about punishment and reinforcement in this article, I am talking about the proper application of learning science, not making dogs scream in pain, cower, shut down, or fear the trainer. Of course, punishment never sounds like a good thing, but it technically means to make a behavior less likely to occur in the future. That is sometimes necessary, and anyone who ever had a dog that needed to stop doing something understands this. But how we stop unacceptable (i.e., dangerous or destructive) behaviors matters a lot. In contrast, reinforcement means making a behavior more likely to occur in the future.

Classic Conditioning

During classic conditioning, a clear association is formed between a previously neutral stimulus (e.g., the word ‘sit’) and an unconditioned response (e.g., the act of sitting). Classic conditioning turns the neutral stimulus into a conditioned stimulus the dog responds to. The understanding of this learning process dates back to 1927 when Russian scientist Ivan Petrovich Pavlov authored his thesis on Conditioned Reflexes: An Investigation of the Physiological Activity of the Cerebral Cortex. Pavlov stumbled upon this instrumental finding while studying dogs’ digestive systems. Given how significant classical conditioning is, this was quite a lucky accident!

Pavlov installed an automatic feeding system in his studies, where a bell would ring before food was dispensed. Initially, the dogs seemed to anticipate the arrival of the food after hearing the bell but would only salivate when the food was in front of them. With time and repetition, the dogs only started salivating at the sound of the bell—even when no food was coming. The sound of the bell produced the same physiological response as the food itself. The bell made the dogs feel the same way the food did. The salivating had become a conditioned response. We are calling this type of learning classic conditioning.

An example is the conditioning of commands in obedience training. Using classic conditioning, a skilled trainer can associate a command word like ‘sit’ with the behavior of sitting. The result is the dog responding correctly to a signal the trainer gives.

Operant Conditioning

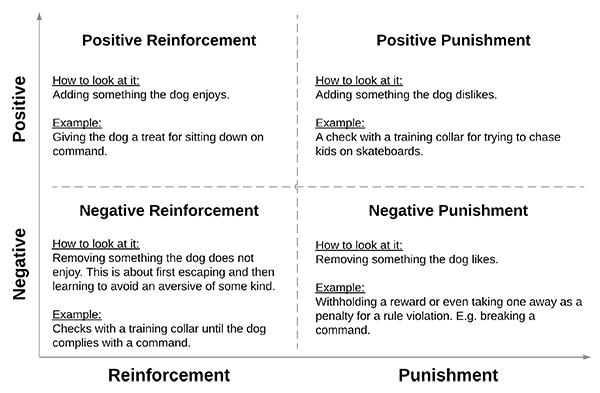

Operant conditioning is another way of shaping behaviors in dog training and about cause-and-effect relationships. Behaviors are encouraged through reinforcement (positive and negative), and behaviors are discouraged through punishment (positive and negative). Operant conditioning builds an association between a behavior and an outcome of that behavior. We are attaching desirable and undesirable consequences to a dog’s behavior. Many more trainers work within this modality than the previous one.

The Quadrant illustrates operant conditioning—a framework also used in human psychology and based on the work of B.F. Skinner.

Over the years, I realized that the terminology used and applied in shaping a dog’s behavior is easily misunderstood. Dog trainers use terms like reinforcement and punishment. These terms can hold negative meanings. In the context of dog training, leaving the everyday meaning of these terms behind helps with understanding the concepts better.

Understanding the quadrant is straightforward once you know the terminology of positive vs. negative and reinforcement vs. punishment as it relates to dogs.

Positive and Negative

Positive refers to adding something, and negative refers to taking something away. It is that simple—not good and bad—it’s just plus and minus. Adding something can be as much petting or a treat as it can be an aversive. It’s similar to taking something away. Examples are withholding a reward or taking the pain away by assisting after an accident. What precisely is being added or taken away is described in the following term.

Reinforcement and Punishment

Reinforcement describes something that makes it more likely that a dog performs a behavior. Punishment describes something that makes it less likely that a dog performs a behavior.

However, punishment should never be confused with cruelty or violence. Many people believe it does, as punishment in human language is rarely positive. In dog training, punishment is used to deliver a penalty for a violation your dog understands.

Any punishment you give is only appropriate if your dog views it as such and understands what it is for. Doing things that might make you feel better but are meaningless to your dog is confusing for your companion. Inappropriate actions can also damage the relationship with your dog. Inappropriate actions are: yelling at dogs out of anger or hurting them for any reason. None of these actions would be considered appropriate punishment in this context.

Those definitions should clarify one thing: reinforcement is used to create or encourage behaviors, and punishment is used to stop or discourage behaviors.

Combining all Components

In dog training, we distinguish four components—the four corners of the quadrant—that every trainer taps into. It is impossible to use only one of these components and expect successful outcomes. Trainers who try are pretty limited in their abilities.

The following example will help clarify these concepts: Many dog owners will recognize the scenario of telling their dog to sit down by saying, sit. This works fine initially, but the dog gets up once you start petting it.

Phase 1: You say sit, and your dog sits down—you start petting it as a reward for good behavior—this is called positive reinforcement, as you are adding something (a petting) your dog likes. Verbal praise is great too. Or you could play with your dog as a reward.

Phase 2: Next, your dog breaks the command and gets back up while you are petting him—you stop petting him, as you don’t want to encourage disobedience—this is called negative punishment as you remove something (the petting) your dog likes.

Phase 3: You repeat the verbal signal sit to mark the mistake and help the dog back into the sitting position with a few taps on its collar—this is called negative reinforcement, as the dog learns to avoid collar taps by staying in the sitting position.

In this basic example, we used three components of The Quadrant to teach your dog not to break the sit command: positive reinforcement, negative punishment, and negative reinforcement.

Example Review

This example highlights why trainers, who claim only to use positive reinforcement, are mistaken. The simple act of stopping to pet your dog for breaking the command is called negative punishment. Trainers, who claim to only work with positive reinforcement, don’t understand the correct terminology of what they are doing. I also have never met anyone who thought stopping to pet a dog was cruel.

The problem with positive reinforcement is how well it works … until it doesn’t.

– Pat Stuart

Understanding these basic concepts allows you to sort out knowledgeable trainers from rookies. Experienced dog professionals understand these concepts, use the correct terminology when discussing your dog, and take the time to explain things.

In some dog training literature and at least one scientific study, you find references that reinforcements and punishments must be delivered within 1 to 1.7 seconds for a dog to make the association. From my 18+ years of professional dog training experience, I disagree with that limit. You have a few seconds. Some of the most respected dog trainers in the world have stated the same in their courses and presentations. As long as there is a continuation between the action and the reinforcement or punishment, your dog will learn.

Understanding Positive Reinforcement

You ask your dog to sit, he does it, and you reward him. You are adding something (i.e., treat, play, affection) to increase the likelihood of future command compliance (reinforcement) with sit. This is called positive reinforcement.

Positive reinforcement means adding something your dog likes. Any reward your dog enjoys is a positive reinforcement of the preceding behavior. However, positive reinforcement requires your dog to do something you like first—the desired behavior. If a dog misbehaves, any kind of reward is misplaced. Many learned that in their first high school psychology lesson. Don’t reward bad behavior.

Positive reinforcement is terrific for teaching new skills. One would have to be an idiot not to use that. But positive reinforcement has limitations, and trainers who restrict themselves to this sub-section of learning science will not be able to work effectively in many areas, especially when dealing with behavioral challenges or competing reinforcers (e.g., squirrels in trees, and so on).

As Marschark and Baenninger, in their 2002 study Modification of Instinctive Herding Dog Behavior using Reinforcement and Punishment, pointed out:

While positive reinforcement can be used exclusively for training certain behaviors, in the context of instinctive behaviors like herding, chasing, or stalking, negative reinforcement and punishment are usually desirable and necessary additions to positive reinforcement techniques.

– Marschark and Baenninger, 2002

Understanding Positive Punishment

Positive punishment is adding something your dog does not like. A typical example is a punishment for disobedience. This could be jumping up, pulling on the walk, or more serious offenses like aggression towards other animals or people. All undesired behaviors must be penalized when they occur so your dog learns when something is unacceptable to you. Punishments can be physical, verbal, or, best, a combination of both in the correct order. These can be pops with a training collar, sounds (e.g., no), or other trained cues.

However, it is imperative only to use punishments your dog understands. It is never acceptable to hurt a dog in meaningless ways because its behavior is frustrating. Punishment is only meaningful if your dog understands it, learns, and changes. Sometimes punishments should be followed by showing your dog what to do instead. However, that is unnecessary when it is just about stopping something unacceptable. For example, if jumping up on visitors is unacceptable, your dog doesn’t have to learn to sit for them instead. It simply has to learn not to jump up.

Only the complete penalty—change—reward cycle helps your dog learn.

Sometimes Punishment is Necessary

Positive punishment is what most animal rights activists take issue with, and as I mentioned before, there are plenty of abusive trainers out there. But at the end of the day, it is all about the execution and how you go about it; it can be good, effective training, or animal cruelty.

When a skilled, experienced trainer teaches you how to punish undesirable behaviors correctly, it will work quickly, your dog’s stress will be minimal, and your dog will be perfectly happy afterward. It shouldn’t be hard to watch. You’ll be happiest with a trainer who cares about your dog’s experience during training.

Some behaviors (i.e., dangerous or destructive) must stop for a dog to be part of a human household. The correct application of appropriate punishment is the fastest way to that goal.

Understanding Negative Reinforcement

Negative reinforcement means removing something your dog doesn’t like. In dog training, that is usually some form of aversive. Negative reinforcement is essentially learning to escape something unpleasant and ultimately avoid it altogether. The goal is for your do to learn how to avoid it, not to keep doing it for months on end.

I touched a hot oven plate when I was maybe eight years old. It hurt. I got some minor burn wounds. They healed. Guess what I didn’t do again? This was a single-event learning experience. It taught me not to touch hot oven plates. This is an excellent example of negative reinforcement or escape and avoidance learning.

Negative reinforcement is one of the major organizing principles of Operant Conditioning and has been extensively studied. It is effective, as it relates to our (and all animals’) fundamental biology of preferring to avoid bad things.

Negative Reinforcement in Dog Training

In dog training, we generally use negative reinforcement to bring a dog into a behavior. E.g., you are heeling your dog, and it gets distracted by something unusual. A few pops on a training collar (aversive) get its attention off the distraction and back onto heeling; that is negative reinforcement. Your dog would prefer the collar pops to stop, and when it comes back into heeling, they stop. The dog learned it could escape the aversive by returning to the activity.

Suppose we further announce the possibility of collar pops beforehand with a verbal signal (i.e., heel). In that case, our dog can learn to avoid the whole process if it comes into behavior when hearing heel. The dog learned how to avoid the aversive.

Because avoiding an aversive activates the same rewards circuit in the brain as getting a reward, negative reinforcement becomes self-reinforcing quickly. For this reason, negative reinforcement is generally considered to create more reliable behaviors than positive reinforcement alone.

Understanding Negative Punishment

Negative punishment means removing something your dog likes. Typical examples include stopping to pet your dog when a command is disobeyed or removing food or toys your dog wants to have.

Negative punishment, like positive punishment, is aimed at reducing the likelihood of a behavior. In this case, by taking something away.

For this to work, two conditions have to be met. First, the dog must care about what you are taking away. Second, you must be able to control it.

A Note on Food: Don’t do this with food by yourself if you are working with a sketchy dog. Hire a professional dog trainer. When it comes to food, this can be pretty dangerous with a food-aggressive animal and carry a high risk of injury.

In Conclusion of Operant Conditioning

The Quadrant illustrates the basic ways dogs learn. For dogs, it’s all quite simple. They are nature on four legs. Humans usually complicate matters by inventing new training methods incompatible with nature’s design.

Understanding how our furry friends learn is the key to resolving behavioral issues and achieving training goals.

Extensive references (including links) to studies on all elements of Operant Conditioning can be found in my article Positive Dog Training.

Of course, other elements impact learning, but exploring all of them goes beyond the scope of this article. Just for sake of comprehensiveness, I want to mention a few additional areas that are highly significant when training dogs:

- Following the laws of classic conditioning (i.e., forming associations)

- Differential reinforcement (i.e., a complex but important strategy)

- What was the dog bred to do? (i.e., genetics)

- What is the dog mentally capable of? (i.e., intelligence)

- What is the emotional state of the dog during learning?

- The learning environment and lesson structure.

4. The Training Approach

All dogs are trainable. It is irrelevant what breed a dog is or what age. The only training restrictions are your dog’s physical limitations and your imagination.

How a dog’s breed factors into training is often misunderstood. In some aspects, understanding the breed is critical; in other aspects, it’s less relevant. The breed informs the genetic blueprint of a dog and what is most likely inherently rewarding. This is critical in designing the optimal reward event for the dog during training—however, this is only the starting point. We still have to assess each dog individually. For example, not all hunting breeds enjoy all hunting activities as much as one expects. They should, but genetics can be a funny thing.

A dog’s breed is also essential in creating a biologically fulfilling lifestyle for the dog. We must provide every dog an outlet for its genetic drives. If we fail to do so, dogs tend to find alternatives to close the gap. Most people don’t appreciate the displacement behaviors dogs come up with. Common displacement behaviors include: digging holes, eating sprinklers, pacing fences, eating through walls, ripping moldings of doors and windows, other destructive behaviors, separation anxiety, other fear behaviors, chasing cars/skateboards/bikes, other aggressive behaviors, and so on.

However, the breed is not that important regarding how we will teach that dog a specific command. In terms of teaching, we can use toys, food, affection, or a combination.

The Different Options

Play-based training is ultimately the most effective way to motivate and train a dog. But it is more challenging to learn. As a result, not as many trainers like doing it or even understand it well enough. Learning how to play with dogs the right way is an art form. Initially, it can also take a while for a dog to get interested in play. This is especially true if the dog has never met a human worth playing with.

Training with food is still the most common way to train. It is much easier to learn the basics of this approach. However, genuinely mastering training with food is almost as complex as training with toys. As a result, a lot of training with food stays at a boring level for dogs. Also, fearful dogs will often not take food from unfamiliar people, and too many trainers don’t know how to change that and give up.

Only rewarding dogs with affection is not as common, but sometimes may be the only way. I had such a case once. It was interesting. Most of the time, this is not enough.

And, of course, we can’t forget the idiots who want to train everything through compulsion. How viewing dogs as opponents and beating them into submission became a thing is a story for another time. This is no way to train a dog!

Conclusion

Aversives in training should only be applied as part of a larger strategy and overall training plan. We use aversives to stop behaviors or to bring a dog back into behaviors the dog already understands. Aversives should not be the sole way of communication. If beating a dog up is all a trainer has to offer, you can’t expect much from the dog in return.

Finally, we don’t get to decide what a dog finds rewarding. It finds rewarding what it finds rewarding. If it’s sniffing dandelions, so be it. Sit – Down – Stay – Okay – Sniff Dandelions.

I hope the information in this article helps you find a skilled trainer who can assist in achieving your training goals. Trainers who misuse basic terms usually also don’t understand how to train reliable behavior in dogs. Trainers who take their job seriously have a broad skill set. They will guide you as to the correct training approach for your dog. The correct training approach for your dog depends on what it responds to and not what you think it should respond to.

Play the Audio